Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer occurs when irregular cells grow in the bladder, the hollow organ that holds urine. It affects men about three times more often than women and occurs most often in people over 65. Our team offers expert, personalized bladder cancer care.

What is cancer?

Cancer starts when cells in the body change (mutate) and grow out of control. To help you understand what happens when you have cancer, let's look at how your body works normally. Your body is made up of tiny building blocks called cells. Normal cells grow when your body needs them. They die when your body doesn't need them any longer.

Cancer is made up of abnormal cells that grow even though your body doesn't need them. In most cancers, the abnormal cells grow to form a lump or mass called a tumor. If cancer cells are in the body long enough, they can grow into (invade) nearby tissues. They can even spread to other parts of the body (called metastasis).

What is bladder cancer?

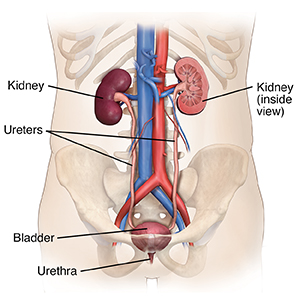

The bladder is a hollow, balloon-like organ in the lower belly (pelvis). It holds urine until it’s passed out of the body. Urine comes into the bladder through 2 tubes called the ureters. Each ureter is attached to a kidney. This is where urine is made. When you pass urine, it comes out through a tube called the urethra. All of these organs make up the urinary tract.

The cell where the cancer starts

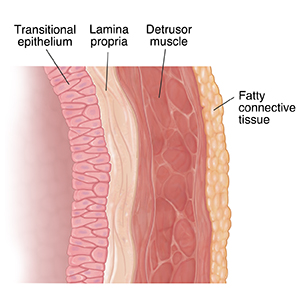

One way to discuss bladder cancer is to describe the kind of cells it starts in. The bladder wall is made up of many layers of cells. It has an outer layer of muscle cells and an inner lining layer of transitional cells. Bladder cancer can affect any one or all of these cells (and layers). These are the 3 types of cells that most commonly become bladder cancer:

- Urothelial cells or transitional cells. These cells make up the tissue that lines the inside of the bladder. This tissue is called the urothelium. Cancer that starts here is called urothelial carcinoma or transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). This is, by far, the most common type of bladder cancer.

- Squamous cells. These look like cells from the surface of the skin. They can start in the bladder if there's a lot of inflammation. Over time, they can become cancer. This type is rare, causing less than 1 in 50 of all bladder cancers.

- Cells that make up glands. This type of bladder cancer is called adenocarcinoma. It’s very rare. Only about 1 in 100 people with bladder cancer has this type.

In rare cases, other cancers can start in the bladder. These include lymphoma, sarcoma, and small cell carcinoma.

How deep is the cancer in the bladder wall

Another way to talk about bladder cancer is by how deeply it spreads into the layers of the bladder wall. This puts the cancer into 1 of 2 groups:

- Nonmuscle invasive. This type of cancer affects only the inner lining of the bladder. (It's urothelial carcinoma or transitional cell carcinoma.) It hasn't grown deeper into the bladder's muscle layer. After treatment, nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer often comes back, often as another nonmuscle invasive cancer.

- Muscle invasive. This cancer affects deeper muscle layers of the bladder and maybe the fatty tissue around the bladder. Invasive bladder cancer is more likely to spread to nearby organs. These can include the kidneys, prostate gland, and the uterus and vagina. It may also spread to the lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are small groups of special cells that fight infections. Almost all squamous cell bladder cancers and adenocarcinomas are invasive.

Subtypes of transitional cell carcinomas

Transitional cell carcinomas (TCCs) may also be described as being either papillary or flat:

- Papillary tumors. These look like small mushrooms and grow into the open part of the bladder. They rarely go deeper into other layers of the bladder. Some types of papillary tumors tend to come back. But they can be removed without damaging the bladder.

- Flat tumors. These don't grow into the open part of the bladder. They spread along the lining.

If either of these grow into the deeper layers of the bladder, it's called invasive TCC.

Talk with your healthcare provider

If you have questions about bladder cancer, talk with your healthcare provider. Your provider can help you understand more about this cancer.

How is bladder cancer diagnosed?

If your healthcare provider thinks you might have bladder cancer, you’ll need certain tests and scans to be sure. Diagnosing bladder cancer starts with your healthcare provider asking you questions. You'll be asked about your health history, symptoms, risk factors, and family history of disease. A physical exam, which may include a rectal or vaginal exam, will be done. This is done to check for tumors that are large enough to be felt.

What tests might I need?

You may get one or more of these tests:

- Urinalysis and urine culture

- Urine cytology test

- Urine tests for bladder cancer tumor markers

- Cystoscopy

- Intravenous pyelogram (IVP)

- CT scan

- Bladder biopsy

Urine tests

Urinalysis and urine culture

This test is done to look for signs of infection or other problems that may be causing your symptoms. You'll need to urinate in a cup for this test. Then your urine is sent to a lab to be tested for blood, certain chemical levels, and signs of infection. The urine is also cultured to see if organisms, such as bacteria, grow. It takes a few days for the test results to come back.

Urine cytology test

For this lab test, your urine is looked at with a microscope. The cells are checked to see if any of them look like cancer or pre-cancer cells.

Urine tests for bladder tumor markers

These tests are used to look for markers or substances that bladder cancer cells make and release into your urine.

Imaging tests

Cystoscopy

This procedure lets your healthcare provider look at the inside of your bladder. It’s the best test for diagnosing bladder cancer.

A very thin, flexible tube is slid through your urethra into your bladder. The tube (called a cystoscope) has a tiny camera and light in it. Saltwater is put into your bladder through this same tube. This fills your bladder so your healthcare provider sees the inside wall or lining. If a change is seen that looks like it might be cancer, a tiny piece may be taken out through the tube and sent for testing. Your provider may also take a urine sample with a bladder wash during a cystoscopy. This is when the saltwater is removed, saved, and checked for cancer cells.

Intravenous pyelogram (IVP)

In this test, a dye is put into your blood through a vein in your arm or hand. As the dye moves through and outlines your kidney, ureters, and bladder, a series of X-rays is taken.

This test is used to find things like tumors, kidney stones, or any blockages. It’s also used to measure blood flow through your kidneys. This test can help to rule out other diseases or check for cancer in other parts of the urinary tract.

CT scan

A CT scan uses a series of X-rays to make pictures of the inside of your body from many angles. CT scans are more detailed than regular X-rays. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis may be used to check for bladder cancer.

During the test, you lie still on a narrow table as it slides through the center of the ring-shaped CT scanner. Then the scanner sends beams of X-rays to your body. A computer uses the X-rays to create many pictures of the inside of your body. These are put together to create a 3-D picture. You may be asked to hold your breath once or more during the scan. You may be asked to drink a contrast dye after the first set of pictures is taken. This dye can help get clearer images. It will pass out of your body over the next day or so through your bowel movements. If the dye is put into your blood through an IV (intravenous) line in your arm, it may cause a feeling of warmth in your body for a few minutes. In rare cases, it can also cause hives or other allergic reactions. Tell the technician if you don’t feel well during the test.

Bladder biopsy

A biopsy is a tiny piece (called a sample) of cells and tissue. A bladder biopsy is often done during a cystoscopy. If your healthcare provider sees something that looks like cancer, a small sample of that tissue can be removed.

Any removed tissue is sent to a special healthcare provider called a pathologist. This provider looks at the tissue under a microscope and does tests on it to check for cancer.

If there is cancer, the biopsy can help tell whether it's just on the inner lining of the bladder or if it’s gone into the deeper layers of the bladder wall.

It takes several days for biopsy results to come back. A biopsy is the only sure way to know if you have cancer and what kind of cancer it is.

Getting your test results

When the results of your biopsy are back, your healthcare provider will contact you. Your provider will talk with you about other tests you may need if bladder cancer is found. Make sure you understand the results and what follow-up you need.

Surgery

Before surgery, you'll meet with a surgeon called a urologist. This is a doctor who specializes in problems with the urinary tract, including the bladder. At this meeting, you’ll talk about the details of the type of surgery to be done, what other organs may need to be removed, and how urine will come out of your body after surgery.

You'll also be able to ask questions and talk about any concerns you may have. For instance, you might want to ask about the risks and possible short- and long-term side effects of the surgery. You may also want to ask when you can expect to return to your normal activities. You might want to know where the scars will be and what they’ll look like.

Your urologist will need to know about all the medicines you take. This includes both prescription and over-the-counter medicines. Tell them if you use any vitamins, herbs, supplements, or marijuana. Also tell them about any illegal drugs you take. This is to make sure you're not taking anything that could affect the surgery. After you’ve talked about all the details with the surgeon, you’ll sign a consent form that says you understand what will be done. It gives the surgeon permission to do the surgery.

To help deal with the information you'll get and to remember all your questions, it helps to bring a family member or close friend with you. You should also bring a written list of concerns. This will make it easier for you to remember your questions. You may also find it helps to take notes.

You might want to get a second opinion before deciding what kind of treatment you'll get. This can help you feel better about the choices you're making. The peace of mind a second opinion gives you may be well worth the effort. Your provider can help you with this.

Types of bladder cancer surgery

Your healthcare provider will use the stage of the cancer to help decide the type of surgery you should have. The stage is the size of the cancer and where it is. Your provider will also consider your personal choices and overall health.

The types of surgery used to treat bladder cancer include:

Transurethral resection (TUR)

This may also be called transurethral resection for bladder tumor (TURBT). In this surgery, all the cancer in your bladder is taken out. But your whole bladder isn't removed. This type of surgery might be done if the cancer is only in the lining of your bladder. TUR can also be done to diagnose bladder cancer and find out how deep it has grown into the bladder wall.

After you get to the operating room, you'll be given medicines called anesthesia. You may get a local anesthesia. This keeps you from feeling what's going on, but you’re still awake. Or you may get general anesthesia. This puts you into a deep sleep and keeps you from feeling pain. You won't need to have any cuts (incisions) made in your skin for TUR. It's done using a special tool called a cystoscope.

The cystoscope is a thin, lighted tube. It's put in through your urethra and slid up into your bladder. Using the cystoscope, your urologist looks at the inside of your bladder, often on a computer screen. If bladder cancer is seen, a tiny tool at the end of the cystoscope can be used to cut out the tumor. After the cancer has been taken out, the area may be burned. Or a laser can be used to stop the bleeding and kill any cancer cells that may be left behind at that spot. All of this is done through the cystoscope.

You may be able to go home the same day. Or you may stay in the hospital a day or so after TUR. A soft tube (catheter) is left in your urethra after the procedure. This tube drains urine from your bladder. It keeps your urethra from getting blocked after surgery. It also helps give your bladder time to heal. It will be taken out in a week or so. Your bladder will then work the way it did before surgery.

You may feel the need to urinate more often when the catheter is first removed. You may feel a little pain when you urinate. There may also be blood or even clots in your urine. These are normal and go away after 1 or 2 days. Call your urologist if you have a lot of pain or bleeding. Also call them if the pain or bleeding doesn't get better in a few days.

There's a good chance that you won't have any cancer left after TUR. But you'll still need to see your urologist every 3 to 6 months for a while. This is because bladder cancers like this often come back. In some cases, TUR may be followed by some type of intravesical therapy. This is when an immunotherapy medicine is put right into your bladder for a few hours.

In follow-up visits, your urologist will look at the inside of your bladder with a cystoscope. This is called a cystoscopy. It uses a thin, lighted tube that's like the one that was used for the TUR. It's put into your bladder through your urethra. You’ll also give urine samples for testing. These tests are done to see if the cancer has come back and find it early if it does.

Partial cystectomy

This surgery may be done if the cancer has spread to deeper tissue under the lining of the bladder, but is small and only in one place. In this case, only the part of the bladder wall with the cancer is removed.

After you get to the operating room, you'll be given general anesthesia. These medicines put you to sleep and keep you from feeling pain. A cut (incision) is made in the skin of your lower belly (abdomen). The urologist takes out the cancer and some of the healthy bladder wall around it. Nearby lymph nodes may be removed, too.

This surgery might be done through many small cuts on your belly instead of a big one. A long, thin tube with camera (called a laparoscope) is put in 1 cut. Long, thin tools are put in the other cuts to do the surgery. This is called laparoscopic surgery.

After the cancer is removed, your healthcare provider will close the hole in your bladder wall with stitches. A soft tube (catheter) is left in your urethra after the procedure. It drains urine out and gives your bladder time to heal. It will be taken out after a week or so. You stay in the hospital for about a week after this surgery. After you heal and the catheter is removed, your bladder works as it did before surgery. But it's smaller, so it may not hold as much urine. A concern with this surgery is that the cancer may come back in another part of your bladder.

You'll have regular follow-up visits with your urologist. The inside of your bladder will be checked with a thin, lighted tube called a cystoscope. This is called a cystoscopy. It allows your provider to look for changes in the lining of your bladder. You’ll also give urine samples for testing and X-rays or scans might be done. These tests are used to see if the cancer has come back and find it early if it does.

Radical cystectomy

This means your whole bladder is taken out during surgery. Nearby tissues, organs, and lymph nodes are also removed. This surgery may be needed if the cancer has spread deeply into the bladder wall or is large or in more than 1 part of your bladder. When all the bladder is removed, you’ll need reconstructive surgery to make a new way for urine to leave your body. All of this is done in 1 surgery.

In people assigned male at birth, the prostate gland and seminal vesicles are also removed. This is because the cancer can come back in these areas. In people assigned female at birth, the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, cervix, and the top of the vagina may need to be removed. Your healthcare provider will talk with you about which organs may need to be taken out. They will also talk with you about side effects and how this surgery will change your body and how it works. If you plan to have children in the future, ask how surgery may affect your ability to have children (fertility).

In the operating room, you’ll be given general anesthesia. These medicines put you to sleep and keep you from feeling pain. A cut will be made in your lower belly (abdomen) to do this surgery. In some cases, the surgery may be done with a laparoscope. This means it's done through many small cuts instead of a big one. A long, thin tube with a camera (laparoscope) is put in 1 cut. Special tools are then put in the other cuts to do the surgery.

Your surgeon must create a new way for urine to leave your body. So, right after your bladder is removed, bladder reconstruction is done. This is covered in the next section. You’ll stay in the hospital for about a week after surgery.

You'll need regular follow-up visits with your urologist after surgery. At first, these visits may be every 3 to 6 months. Over time, they'll be less often. Blood and urine tests and imaging scans will be done. They're used to watch for signs that the cancer has come back and find it early if it does.

Reconstructive bladder surgery

Urine made by your kidneys will need to be stored and moved out of your body in a new way after your bladder is removed. There are many ways to rebuild a "bladder." This is called reconstructive surgery. Your surgeon does reconstructive surgery right after you have your bladder removed (radical cystectomy).

Right after bladder reconstructive surgery, long, thin drainage tubes that are put in the ureters will come out of your body. These may be left in for 2 to 3 weeks. They keep urine away and allow the tissues to heal where they're attached to the piece of intestine or to an opening (called a stoma or urostomy) that's been made in your belly. Scans with dye will be done to see how well your new bladder has healed. Your provider will also make sure there isn't any urine leaking inside your body before taking out the drainage tubes.

There are 2 main types of reconstructive surgery:

Incontinent urinary diversion

After this type of surgery, you’ll wear a bag on the outside of your body to collect urine.

This procedure creates an ileal conduit and an opening (called a stoma or urostomy) that's been made in your belly. To do it, your healthcare provider takes out and cleans a small piece of your intestine (from the part called the ileum). The2 ends of your ileum are then sewn back together. One end of the removed piece is connected to your ureters. These are the tubes that carry urine out of your kidneys. The other end is connected to the skin in your lower right belly where a stoma has been made.

Urine then drains from the kidneys, through the ureters, into the ileal conduit (piece of intestine), and out the urostomy. It goes into a plastic bag that sticks to your skin. Urine will slowly drain out all the time, and you'll need to empty the bag several times a day.

Once the tubes are out, you'll use a sticky plastic pouch that goes over the stoma. When the pouch is full, you empty the urine through a valve at the bottom of it. You’ll need to change the pouch every 3 to 5 days. A special nurse (called an enterostomal nurse) will teach you how to care for your urostomy. The nurse will teach you how to keep the urine bag, tubes (catheters), and stoma clean. The nurse will also give you advice on lifestyle issues, such as having sex or managing your urine bag at work.

Continent urinary diversion

This surgery creates a new bladder. This way, you can control when urine leaves your body and do not have to wear a bag.

There are 2 main types of continent diversions:

- Cutaneous continent diversion. This is drained through a hole (stoma) in your belly. This is done with a catheter several times a day.

- Orthotopic neobladder. This is the creation of a new bladder that’s emptied through your urethra the same way you did before surgery.

During surgery, a piece of your intestine is removed, cleaned, and connected to your ureters. This is done to make a new path for your urine to flow. The other end of the pouch made from the intestine is attached to a hole (stoma) made in the skin over your belly. Your surgeon then creates a 1-way valve that allows you to drain the pouch several times a day. You do this by putting a catheter in through the stoma. Urine drains out of the pouch into a container. You can then flush the urine in the toilet. Many people prefer a continent diversion because they don't need to wear a urine collection bag on the outside of their body all the time.

After the operation, urine will flow through the ureters into the pouch inside your body. The pouch will hold about a pint of urine a few months after the surgery. It will hold more urine as time goes by. You’ll learn to recognize what it feels like when the pouch is getting full. Then you’ll pass a catheter into the stoma to get the urine out. For a few weeks after the surgery, you'll likely need to drain the pouch every few hours. As the pouch stretches, you'll probably need to empty it every 4 to 6 hours.

An enterostomal nurse will teach you how to care for the stoma and use a catheter to get urine out. The nurse will also give you advice on lifestyle issues, such as having sex or emptying your diversion at work.

Neobladder

This surgery may also be called orthotopic continent urinary reconstruction. You can only have it if your urethra was not removed during the original surgery. A neobladder is a bladder substitute.

A piece of your intestine is removed and used to create a pouch to hold urine. The pouch is the new bladder (neobladder). One end is attached directly to your ureters. The other end is attached to your urethra. This means you pass urine through your urethra, just like you did before surgery. Compared with other reconstructive surgeries, this type is most like your normal urinary tract.

Many people who have a neobladder say they feel the same urge to urinate as they did before surgery. But it may take you a while to learn the sensations that mean you need to urinate. Right after surgery, you’ll have a catheter to drain out urine as your body heals. Urine control does not come right away after your catheter is taken out. You’ll learn the routine you should follow to help train your new bladder.

The ability to control urination during the day is better than 90% with a neobladder. Your ability to control urine flow at night may not be quite as good, especially in the first 6 to 9 months after surgery. You may be able to manage the problem by drinking less before bedtime. Another option is a condom catheter that attaches to the penis like a condom and connects to a tube that collects urine in a bag.

Recovering at home

Make sure you know how to take care of yourself after surgery and are able to manage the way you have to get urine out of your body. Also be sure you have supplies and know where to get more. It may help to have someone learn along with you, so you have a helper and support person at home.

When you get home, you may get back to light activity. But you should not do any strenuous activity for 6 weeks. Your healthcare team will tell you what kinds of activities are safe for you while you heal.

When to call your healthcare provider

Let your healthcare provider know right away if you have any of these problems after surgery:

- Bleeding

- Redness, swelling, or fluid leaking from the incision site

- Fever

- Chills

- Irritation, redness, or swelling around the stoma

- Damage or injury to the stoma

- A blockage of urine flow

The physical and emotional changes from your cancer surgery may be significant. Ask your healthcare team for resources that will help you and your family manage the physical effects of cancer treatment, and also the mental and emotional changes.

Call your healthcare provider or stoma nurse if you have any problems. Know what to do and have a number to call if you have problems or questions after hours or on weekends or holidays.