Understanding Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs)

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are a type of abnormal heartbeat (arrhythmia). They are commonly found in people of all ages.

How PVCs happen

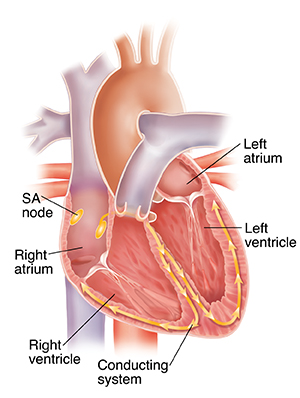

Your heart has 4 chambers: 2 upper atria and 2 lower ventricles. Normally, a special group of "pacemaker" cells begins the signal to start your heartbeat. These cells are in the sinoatrial (SA) node in the right atrium. The signal quickly travels down your heart’s conducting system. It moves to the left and right ventricle. As it travels, the signal sets off nearby parts of your heart to contract. This allows your heart to squeeze in a coordinated way.

During a PVC, the signal to start your heartbeat instead comes from one of the ventricles. This signal is premature, meaning it happens before the SA node has had a chance to fire. The signal spreads through the rest of your heart, causing a heartbeat. If this happens very soon after the previous heartbeat, your heart will push out very little blood. This causes a feeling of a pause between beats. If it happens a little later, your heart pushes out an almost normal amount of blood. This leads to a feeling of an extra heartbeat. So the heart has a “premature” heartbeat in between normal heartbeats.

What causes PVCs?

Most often, PVCs are harmless . But certain things can help set off a premature signal in the ventricles. These include:

-

Advancing age

-

Reduced blood flow to your heart (such as coronary artery disease)

-

Scarring after a heart attack

-

Electrolyte problems, such as low sodium or potassium levels

-

Caffeine

-

Alcohol

-

Nicotine

-

Illegal drugs, such as cocaine and methamphetamine

-

Increased adrenaline, such as with anxiety

-

Certain medicines, such as digoxin

- Endocrine (hormone) problems, such as hyperthyroid (too much thyroid hormone)

Many heart conditions raise the risk for PVCs. These include:

-

High blood pressure

-

Heart attack

-

Coronary heart disease

-

Dilated cardiomyopathy

-

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

-

Congenital heart disease

-

Heart failure

They often happen in people without any heart disease. But PVCs are somewhat more common in people with some kind of heart disease.

What are the symptoms of PVCs?

Most people with occasional PVCs don’t have symptoms. The more PVCs you have, the more likely you are to feel them. When symptoms do happen, they are usually minor. Symptoms may include:

-

An awareness of the heart beating

-

A fluttering or flip-flop feeling in your chest

-

Feeling of a "skipped" or "extra" heartbeat

-

Dizziness and near-fainting

-

A pulsing sensation in the neck

PVCs may cause more severe symptoms if you have another heart problem, such as heart failure.

How are PVCs diagnosed?

Your healthcare provider will ask about your health history and give you a physical exam. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is the main test for diagnosis. This test records the electrical activity of your heart. During an ECG, small pads (electrodes) are placed on your chest, arms, and legs. Wires connect the pads to a machine, which records your heart’s electrical signals. This test allows your provider to look at the signal of your heartbeat for a brief time. Any PVCs that occur during this time will show up on the ECG. In some cases, your healthcare provider might advise at home or portable ECG monitoring over a few days or even weeks. This can help to diagnose PVCs that don’t happen often. There are several types of heart monitors:

-

Holter monitor. This monitor is a small box with wires connected to pads on your chest. You wear it for 1 to 2 days. It provides a constant recording of heart activity. After the test is done, your healthcare provider analyzes the recording.

-

Event monitors. These monitors are also small boxes with wires connected to pads on your chest. They are generally worn for 3 to 4 weeks. But they can be used for several months. One kind is a memory loop recorder. This monitor records constantly. But it stores the recording only when you press a button. The other kind is a credit card-sized recorder. This monitor is turned on only during an episode. With both types, you send the recordings of symptoms to your healthcare provider over the phone.

- Mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry. This type of event monitor is usually used for up to 30 days. It uses cell phone technology to send data in real time to a monitoring center where trained technicians can review it. Or it can contact a healthcare provider for a life-threatening problem.

- Patch monitor. This is a small self-contained adhesive patch that can record your heart rhythm for up to 2 weeks.

- Insertable (or implantable) cardiac monitor. This small device is implanted under the skin. It can be used to keep track of the heart rhythm for several years.

- Commercially available wearable heart rhythm monitors . These include smartwatches or wristbands. They may be useful for finding abnormal heart rhythms.

These may be the only tests your healthcare provider will need. You may need more testing if you have PVCs often, or many in a row. Your provider may look at other causes, including possible heart problems. These tests might include:

-

Echocardiography. This test uses ultrasound to evaluate your heart’s structure and function.

-

Cardiac stress testing. This test checks how your heart responds to exercise and to evaluate heart artery blood flow.

-

Cardiac CT or MRI. These imaging tests make detailed pictures of the heart.

-

Blood tests. This is done to check electrolyte and thyroid levels.